Confessions of a Skeptic: Why Your ESG Fund Might Be Part of the Problem

Why Your 'Green' Fund Might Be Full of Big Oil and Fast Fashion, and What to Do About It.

The Great Green Gold Rush

Let’s be honest. You’ve probably had that moment, staring at your investment portfolio, feeling a slight, nagging pang of guilt. You want your money to grow, of course—retirement isn’t going to fund itself. But you also want it to do good. You want to invest with a clean conscience, to know your capital isn’t paving the way for a dystopian future. Wall Street, ever the obliging servant, has heard your prayers. It has presented a shimmering, multi-trillion-dollar solution on a silver platter: the ESG fund. It’s the kale smoothie of finance—effortlessly virtuous, endlessly marketable, and designed to make you feel good about your choices.

The promise is intoxicating. ESG, which stands for Environmental, Social, and Governance, is sold to the public as a grand unification theory for ethical capitalism. It’s a way to align your portfolio with your values, punishing the corporate villains, rewarding the saints, and—the real kicker—maybe even making a tidy profit along the way. It’s presented as the ultimate win-win-win, a chance to save the world from your sofa.

But what if this whole glorious enterprise is, as one former BlackRock CIO for sustainable investing bluntly put it, little more than "the smoke and mirrors of ESG investing"? What if it’s just "neoliberalism with moral satisfaction draped around it"? The uncomfortable truth is that a reliance on simplistic ESG funds often allows well-meaning investors to feel virtuous while changing precious little. It has become what critics call a "dangerous placebo," a feel-good distraction that delays the real, difficult work of creating change.

This is a confession, a peeling back of the curtain on the great green gold rush. We will explore three fundamental flaws in the ESG industrial complex: the chaotic and misleading nature of the ratings themselves, the feel-good fallacy of selling off "bad" stocks, and finally, a guerrilla guide to what a concerned investor can actually do to make a difference. It’s time to move beyond the marketing gimmick and get our hands dirty.

Part I: The First Confession – The Alphabet Soup of Virtue is a Mess

The entire edifice of ESG investing rests on a single foundation: the ratings. These scores, assigned by a host of competing agencies, are supposed to be our objective guide, separating the corporate angels from the demons. The problem? The foundation is built on quicksand.

The Aggregate Confusion Problem

If you ask different credit rating agencies like Moody’s or S&P about a company's debt, you’ll get a remarkably consistent answer. Studies have found that their ratings agree 99% of the time. Now, ask different ESG rating agencies about the same company's "goodness" score. The agreement plummets to a range of just 38% to 71%. This isn't a minor statistical wobble; it's a systemic failure that researchers have dubbed "aggregate confusion". It means there is no objective, agreed-upon definition of what "good" even looks like. The data, as an MIT research project concluded, is fundamentally "noisy"—like trying to listen to a lecture during a construction project. An investor relying on these ratings isn't just navigating with a compass; they're navigating with a compass that spins wildly depending on who manufactured it.

Deconstructing the Chaos: Why the Ratings Disagree

This divergence isn't random. It stems from deep, structural disagreements on how to measure virtue. There are three main culprits:

Scope Divergence: The agencies don’t even agree on what attributes to measure. One rater might include a company’s lobbying activities or its approach to climate risk management in its assessment, while another completely ignores it. It’s like judging a baking competition where one judge tastes for sweetness, another checks for presentation, and a third only cares about the oven temperature.

Measurement Divergence: This is the biggest driver of disagreement, accounting for a staggering 56% of the total divergence. Even when agencies look at the same attribute, they use wildly different yardsticks. To assess labor practices, for instance, one rater might analyze employee turnover rates, while another counts the number of labor-related lawsuits filed against the company. Both are plausible metrics, but they will inevitably lead to different conclusions.

Weight Divergence: Finally, agencies assign different levels of importance to the factors they do measure. Is a company's diversity policy more or less important than its water usage? Is strong corporate governance more critical than product safety? The answer depends entirely on which rating agency you ask.

The Garbage In, Gospel Out Data Pipeline

The confusion is compounded by a simple, damning fact: much of the data going into these ratings is junk. A huge portion of ESG data is self-reported by companies themselves, is often unaudited, and lacks any kind of standardization. This creates a powerful incentive for "greenwashing," where companies selectively disclose positive information and hire expensive consultants to fill out questionnaires in the most flattering light imaginable. A 2023 poll of 420 professional investors found that 71% view this "inconsistent and incomplete" data as the single biggest barrier to meaningful ESG investing.

The system is structurally biased, favoring large, European, and English-speaking companies that have the financial resources and specialized teams to play this disclosure game effectively. It's a classic case of "garbage in, gospel out," where flawed data is fed into opaque algorithms, which then spit out a score that is treated as an objective truth by the market.

The Fundamental Bait-and-Switch

Perhaps the most deceptive part of the entire ESG fund industry is a subtle but profound bait-and-switch at its very core. Most retail investors buy an ESG fund believing it invests in companies that have a positive impact on the world. This is the promise that is marketed to them. However, the dominant methodology used by major ratings providers like MSCI and Sustainalytics is not designed to measure a company's impact on the world. Instead, it is designed to measure the world's potential ESG-related risk to the company's bottom line.

This is a crucial distinction. A company can be a massive polluter but still receive a stellar ESG rating if it has robust policies in place to manage the financial risks associated with that pollution, such as future carbon taxes or regulatory fines. The rating is not about the company's virtue; it's about its resilience to financially relevant ESG risks. It’s a tool built for institutional risk management that has been cleverly repackaged and sold to the public as a tool for ethical change. It’s not a bug in the system; it's a feature.

Case Study: The Unholy Saints of ESG

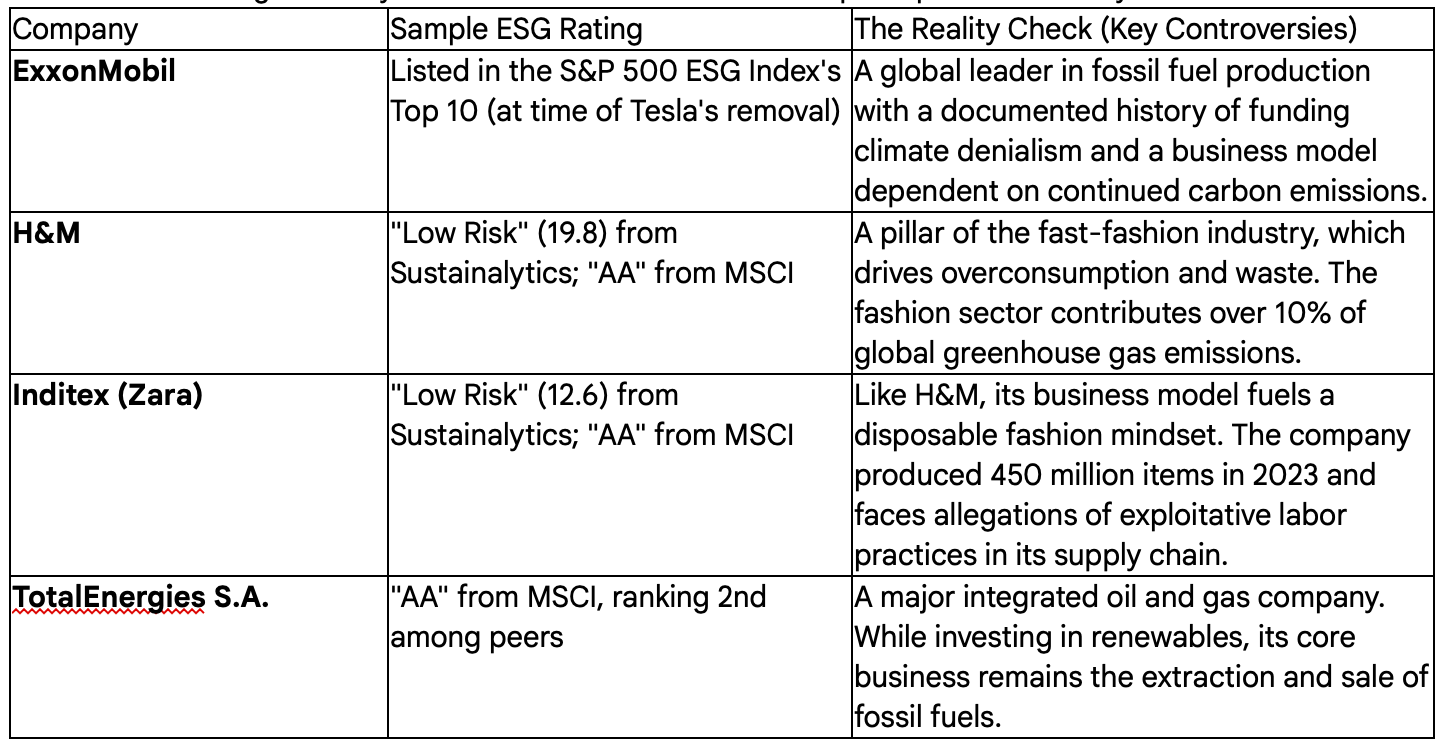

This flawed system leads to some truly head-scratching outcomes. Oil and gas majors, the poster children for environmental damage, can and do receive high ESG marks. Companies like Royal Dutch Shell, TotalEnergies, EQT, and Diamondback Energy often get favorable ratings. Why? Because they might be investing a fraction of their capital in renewable energy projects or, more commonly, because they have strong governance policies for managing the risks inherent in their industry. The rating rewards them for putting on a hard hat, not for stopping the drilling.

The same absurdity applies to fast fashion. Giants like H&M and Inditex (the parent company of Zara) receive "Low Risk" ESG ratings from major providers like Sustainalytics. This is despite their entire business model being predicated on hyper-consumerism, disposability, and a supply chain plagued by concerns over labor practices. The fashion industry is responsible for over 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet these companies are praised for their use of some recycled materials, their public sustainability commitments, and their issuance of "sustainability-linked bonds". The ratings focus on these peripheral activities, effectively ignoring the destructive core of the business model itself. As one analysis noted, some funds include them simply because they aren't "obvious polluters" like a steel mill, prioritizing a narrow view of the 'E' over the 'S'.

Case Study: The Tesla Paradox - When the System Short-Circuits

If you need one story to perfectly encapsulate the absurdity of the ESG rating system, look no further than Tesla. In May 2022, the S&P 500 ESG Index, a widely followed benchmark for "sustainable" companies, kicked Tesla off its list. Yes, Tesla—the company whose entire mission is to accelerate the world's transition to sustainable energy.

The official rationale from S&P was a masterclass in missing the forest for the trees. It had little to do with Tesla's world-changing environmental impact. Instead, the decision was based on its relatively poor scores on Social and Governance metrics. These included claims of racial discrimination and poor working conditions at its Fremont factory, and its handling of federal investigations into accidents involving its Autopilot feature.

And the punchline? At the very same moment Tesla was being excommunicated, fossil fuel behemoth ExxonMobil was proudly listed among the index's top 10 constituents.

This case is the perfect illustration of how the system fails. A myopic, box-ticking approach that treats E, S, and G as separate, unrelated silos can lead to conclusions that defy all common sense and betray the very spirit of what investors believe they are supporting. A furious Elon Musk took to Twitter, calling ESG a "scam". And while his motives may be self-serving, his outrage captured the legitimate frustration and confusion that this broken system engenders in so many.

Part II: The Second Confession – The Illusion of Divestment

If the ratings are a sham, then surely the answer is to take matters into your own hands. The most common advice is to simply sell your shares in "bad" companies—a strategy known as divestment. It feels decisive, moral, and clean, like quitting a country club after discovering its members are puppy-kickers. Proponents often point to the successful anti-apartheid divestment movement of the 1980s as proof of its power. But this feel-good impulse is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how modern markets work.

How the Market Actually Works

Here is a simple, brutal fact that is the stake through the heart of the divestment argument: when you sell a stock on the open market, the company doesn't feel a thing. You are not selling your shares back to the company; you are selling them to another investor who was waiting to buy them. The company raised its capital during its initial public offering (IPO). The billions of shares traded every day on secondary markets like the NYSE or NASDAQ are just investors swapping ownership stakes with each other. Changing who owns the shares does nothing to alter the company's underlying profitability or its day-to-day operations. You haven't punished the company; you've just engaged in a transaction with a stranger.

The Unintended Consequence: Passing the Buck to Bad Actors

This leads to a deeply ironic and counterproductive outcome. When conscientious investors sell their shares en masse, who is on the other side of that trade, happily buying them up? Often, it is investors who are completely indifferent to ethical concerns, or even actively hostile to them. The rise of "anti-ESG" investing firms that proudly specialize in "sin stocks" like tobacco, weapons, and fossil fuels means there is always a ready buyer.

So, the net effect of divestment is not to starve a company of capital. The net effect is to consolidate ownership in the hands of the very people with the least incentive to push for positive change. You have loudly and proudly given up your seat at the table, and an investor who fundamentally disagrees with everything you stand for has eagerly taken it, probably at a slight discount.

The Moral Placebo Effect

The act of divesting provides a powerful, but ultimately false, sense of accomplishment. This psychological satisfaction—this "moral placebo"—can dangerously reduce an investor's motivation to engage in more difficult but far more effective forms of action. Why bother with the hard work of lobbying for a carbon tax, supporting shareholder resolutions, or engaging in a proxy fight when you've already "purified" your portfolio and washed your hands of the problem?

Divestment also conveniently shifts the blame for vast, systemic problems onto a handful of corporate "villains". It allows us, as consumers, to feel blameless for the fossil fuels we burn and the products we consume, because we've pointed the finger at the companies that supply them. It is a symbolic act that feels righteous but is ultimately a counterproductive distraction from addressing the root causes of these urgent problems.

Ultimately, ownership is a form of leverage. It is a voice, however small, in the future of a company. Selling your shares is not an act of power; it is an act of abdication.

Part III: The Third Confession – A Guerrilla Guide to Actual Impact

So, the ratings are a mess and divestment is a dead end. It would be easy to throw up your hands in despair. The bad news is that the easy path—buying a fund with a green leaf on it—is an illusion. The good news is that there are other paths. They are harder, more demanding, and require more effort, but they actually lead somewhere. This is the guide for the investor who wants to graduate from passive virtue to active values.

Alternative 1: The Activist's Playbook – Wielding Your Ownership

Instead of abandoning your ownership, you can wield it like a weapon. The most dramatic proof of this strategy's power is the story of Engine No. 1 versus ExxonMobil.

It was a true David-and-Goliath tale. In late 2020, a tiny, newly-launched impact hedge fund named Engine No. 1, holding a minuscule 0.02% of Exxon's shares, announced it was taking on the fossil fuel giant. Their goal was to replace four members of Exxon's board with their own, more climate-conscious directors.

Crucially, their argument was not purely moral. They framed their campaign in the language of Wall Street: cold, hard finance. They argued that Exxon's stubborn refusal to plan for a low-carbon future and its continued massive spending on fossil fuel exploration represented an existential threat to long-term shareholder value. This was a brilliant strategy. It wasn't about hugging trees; it was about protecting pensions. This financial case allowed them to build a powerful and unlikely coalition, convincing behemoth institutional investors like BlackRock, Vanguard, and the California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS) to join their cause.

The climax came at Exxon's annual shareholder meeting in May 2021. In a stunning, "watershed" upset, Engine No. 1 won. Shareholders voted to install three of the four dissident directors onto Exxon's board. A tiny fund with a $12.5 million campaign budget had successfully forced change at one of the most powerful corporations on earth. This story is the ultimate rebuttal to the powerlessness of divestment. It proves that engagement is not a polite suggestion box; it is a potent tool for forcing change from within. It shows that even a small stake, when combined with a smart strategy and a broad coalition, can move mountains.

Alternative 2: The Bespoke Portfolio – Building Your Own Ark with Direct Indexing

If shareholder activism is about changing the giants from within, direct indexing is about achieving personal portfolio purity. Think of a standard index ETF as a pre-packaged fruit basket from the supermarket. You get the apples, the oranges, and the weird, waxy pear you never eat. With direct indexing, you walk into the market and buy the individual fruits yourself, allowing you to toss out any you don't like. You own the actual stocks directly in a separately managed account, not a share of a fund that owns the stocks.

This approach offers two superpowers that traditional funds can't match:

Radical Customization: This is the main event. You can exclude any company, sector, or industry that violates your personal values—far beyond the blunt, often nonsensical exclusions of a typical ESG fund. Don't like a company's labor practices? Out. Object to a firm's political donations? Gone. This gives you granular control to build a portfolio that truly reflects your beliefs.

Tax-Loss Harvesting: This is the financial sweetener, often referred to as "tax alpha." Because you own hundreds of individual stocks, you can sell the specific ones that have lost value to offset capital gains from winners elsewhere in your portfolio. This is a powerful tax-management tool. Even in a fantastic year for the S&P 500, like 2023 when it was up over 26%, more than 170 of its constituent stocks were actually down for the year, creating a wealth of harvesting opportunities for a direct indexer. This granular harvesting is something a packaged fund simply cannot offer to its shareholders.

This strategy, once the exclusive domain of the ultra-wealthy, is becoming increasingly accessible to retail investors thanks to the elimination of trading commissions and the advent of fractional share trading. Platforms like Fidelity Managed FidFolios now offer direct indexing with account minimums as low as $5,000. Of course, there are trade-offs. It's more complex than buying a single ETF, can lead to more complicated tax forms, and if you customize too heavily, your returns may drift away from the benchmark index you started with. It requires a more hands-on approach than the set-and-forget simplicity of an index fund.

Alternative 3: The Purist's Path – Funding the Future Directly

The final, most potent alternative is to step outside the public markets entirely. This is about investing in private companies whose entire reason for being is to solve a major environmental or social problem. For these ventures, impact isn't a feature, a marketing angle, or a risk to be managed—it is the core business model.

The world of private impact investing is teeming with innovative companies building the future we claim to want. Consider firms like:

Agronutris: A French biotech company using insects to create sustainable animal feed, reducing the strain of aquaculture on our oceans.

Naïo Technologies: A firm that builds autonomous agricultural robots to weed fields, drastically reducing the need for chemical herbicides.

Vestack: A construction company that uses bio-sourced materials to build low-carbon buildings, cutting construction time in half and reducing CO2 emissions by two-thirds.

Norsepower: A Finnish company that retrofits cargo ships with giant, spinning "rotor sails" that harness wind power to reduce fuel consumption and decarbonize the shipping industry.

Nuventura: A German firm that has invented a new technology for energy grid switchgears that eliminates the use of SF-6, a "forever gas" with a greenhouse effect 25,000 times more potent than CO2.

Admittedly, this is the most difficult path for the average investor. Access to these opportunities usually comes through specialized private equity or venture capital funds. However, for those with the means and the risk tolerance, researching firms like Lowercarbon Capital, Breakthrough Energy, Astanor Ventures, and Planet A Ventures can be a starting point to finding funds that are directly financing these world-changing solutions.

These three alternatives are not mutually exclusive. They represent a spectrum of engagement. Direct indexing is about achieving personal portfolio purity. Shareholder activism is about driving systemic reform from within existing corporate giants. And private impact investing is about fostering systemic creation by building the new, sustainable economy from the ground up. A truly committed investor can, and perhaps should, engage across this entire spectrum, creating a multi-pronged strategy that is infinitely more powerful than the single, flawed act of buying an ESG fund.

Conclusion: From Passive Virtue to Active Values

We have confessed that the ESG ratings are a chaotic, misleading mess. We have confessed that the act of divestment is a hollow, feel-good gesture that often does more harm than good. And we have confessed that achieving real impact requires getting your hands dirty.

The seductive convenience of the ESG fund has been a trap. It has allowed the financial industry to successfully monetize our good intentions, charging higher fees for products that often perpetuate the very systems we wish to change. It is a marketing triumph but an ethical and practical failure. It has lulled us into a state of passive virtue, making us feel like we are part of the solution when we are merely consumers of a cleverly branded product.

The ultimate message, however, is one of empowerment. The time has come to stop being passive consumers of financial products and become active, engaged owners of capital. Demand transparency. Question the labels. Embrace complexity. The power to create genuine, measurable change is available to you, but it is not for sale in a convenient, low-cost ETF. Whether it's by meticulously curating your own portfolio through direct indexing, joining a proxy fight to hold a corporate board accountable, or funding a disruptive startup that is building a better world, that power must be actively, thoughtfully, and courageously seized.